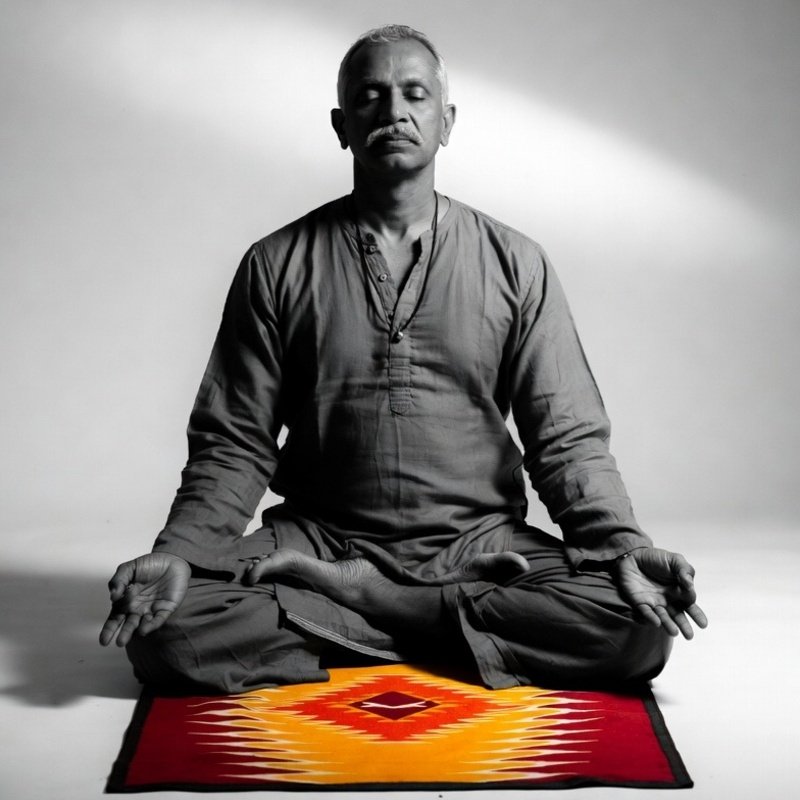

In yoga, every inward journey begins with an outward preparation. Before the breath is refined, before the mind grows still, it begins with your mat, for it is the place where the body learns to sit, settle and abide.

The Sanskrit word āsana is often translated today as “posture,” commonly understood as physical poses practised on the mat. Yet in the classical yogic tradition, āsana carries a quieter and more foundational meaning. Derived from the root ās, meaning to sit or to abide, āsana refers to the seat. The word “āsana” is used to refer to both the manner in which one sits (or the posture one assumes) for meditation & yogic practice, and also to the physical seat (rug or mat).

Āsana in the Classical Yogic Understanding

In the classical system of Aṣṭāṅga Yoga described by Patañjali in the Yoga Sūtras, yoga is presented as an eight-limbed path (aṣṭa = eight, aṅga = limb).

“Yama-niyama-āsana-prāṇāyāma-pratyāhāra-dhāraṇā-dhyāna-samādhayo’ṣṭāv aṅgāni” – Yoga Sūtra 2.29

Translation: Yama, niyama, āsana, prāṇāyāma, pratyāhāra, dhāraṇā, dhyāna, and samādhi —these are the eight limbs of yoga.

Āsana is one of the eight limbs of yoga. However, it is not merely a position the body assumes, but a state in which the body becomes steady enough for awareness to turn inward.

Patañjali defines āsana in the Yoga Sūtras with striking simplicity:

“Sthira sukham āsanam” – Yoga Sūtra 2.46

Āsana, he says, is that posture which is steady (sthira) and comfortable (sukha). Note that there is no emphasis here on complexity, flexibility, struggle or effort. Instead, the focus is on a seat that can be maintained without disturbance, allowing the practitioner to remain still, alert, and at ease.

Patañjali further notes that mastery of āsana frees one from the disturbances caused by dualities such as heat and cold, pleasure and pain (Yoga Sūtra 2.48). This reveals the deeper purpose of āsana: to create a body that does not interfere with meditation.

Why the Physical Seat Matters in Yoga and Meditation

In yogic physiology, the human body is understood as a vessel of prāṇa, the vital life force that animates both body and mind. During meditation, prāṇāyāma, mantra, or Kriyā Yoga practices, prāṇa begins to move more consciously through subtle channels known as nāḍīs.

The seat plays a crucial role in this process.

Traditional yogic teachings advise against practising directly on bare ground. While the earth is grounding, it is also absorbent. When prāṇa is generated through disciplined practice, sitting directly on the floor is believed to allow subtle energy to dissipate downward, weakening the effects of meditation.

For this reason, classical texts and lineages recommend sitting on an intermediate layer that insulates energy.

Historically, this included:

- Kusha grass mats

- Woollen rugs

- Folded cotton cloths

In modern practice, the yoga mat serves a similar purpose. Though not mentioned in ancient texts, its function aligns with traditional principles:

- It insulates the body from the ground

- Reduces unconscious muscular effort by providing stability

- Supports steadiness in seated postures

- Creates a defined, intentional space for practice

Thus, while materials have changed, the wisdom remains the same.

Guidance from Classical Texts

The Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā underscores the importance of āsana as the foundation for all higher practices:

“Having mastered āsana, one attains steadiness of body and freedom from disease.” — Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā 1.17

Seated postures such as Siddhāsana, Padmāsana, and Svāstikāsana are praised not for their outward form, but for their ability to stabilise the body and support prolonged stillness. The text repeatedly emphasises that the best āsana is one in which the practitioner can remain motionless and attentive for extended periods.

In Kriyā Yoga traditions, special importance is given to the seat. Teachers often stress that a stable base, aligned spine, and insulated seat create the ideal conditions for prāṇa to refine and ascend through the suṣumṇā nāḍī. An unstable or uncomfortable seat draws attention outward; a proper āsana allows awareness to turn inward naturally.

Why the Āsana or Mat Is Not Shared

Traditional yoga also advises that one’s āsana or mat should not be shared with others, particularly when used for regular meditation or inner practices. This guidance arises from several complementary understandings:

1) The yogic seat is believed to absorb subtle impressions (saṁskāras). Through repeated practice, the mat or seat comes into contact with breath patterns, emotional states, nervous system activity, and prāṇic movement. Sharing it may introduce foreign impressions that subtly disturb mental steadiness.

2) Over time, the seat becomes energetically attuned to the practitioner. Just as the body adapts to a regular posture, the āsana becomes familiar to the nervous system, helping the practitioner settle more quickly into stillness. Using the same seat consistently supports continuity in practice, whereas sharing it disrupts this subtle alignment.

3) There is also a psychological dimension. When a mat is used exclusively by one practitioner, the mind begins to associate it with silence, discipline, and inwardness. Simply sitting on it can signal the transition from outer activity to inner awareness. Sharing the mat weakens this conditioning and the sense of sacredness attached to one’s sādhana.

Importantly, this is not a rule rooted in fear or superstition. For casual group classes, shared mats pose no issue. But for sustained meditation and serious yogic practice, traditions recommend one practitioner, one āsana.

The Mat as a Threshold Space

Beyond its physical and energetic role, the mat serves as a threshold. Stepping onto it marks a conscious pause: a turning away from distraction and toward presence. Over time, the mat becomes more than a surface. It becomes a reminder of intention, discipline, and inner inquiry.

In this way, āsana forms the bridge between the outer limbs of yoga and the inner ones. When the body is steady, the breath becomes subtle. When the breath is refined, the mind grows quiet. Meditation then arises not through force, but naturally.

Returning to the Essence of Āsana

Modern yoga often celebrates movement, strength, and flexibility. The classical teachings gently remind us of something simpler and deeper: the art of sitting well.

Āsana, in its truest sense, is not about how much the body can do, but about how completely it can be still. By giving care to our seat: by honouring the mat, the posture, and the practice, we create the conditions for receptivity or in other words, for meditation to happen organically.

And so, in yoga, as in all inner disciplines, it begins with your mat.