Yoga is a word that has been in vogue for a number of years now. I think from the time the West got interested in Yoga, it has become a very popular word. Well, the fact is, for a thousand years or more, Yoga has been practised in this country and the practitioners have been called Yogis.

How do you distinguish a Yogi? Does a Yogi wear special clothes? Is it necessary for a Yogi to wear a rosary around his neck? Is a Yogi always around with special paraphernalia like a Kamandalu or wearing wooden sandals and matted hair? Not at all!

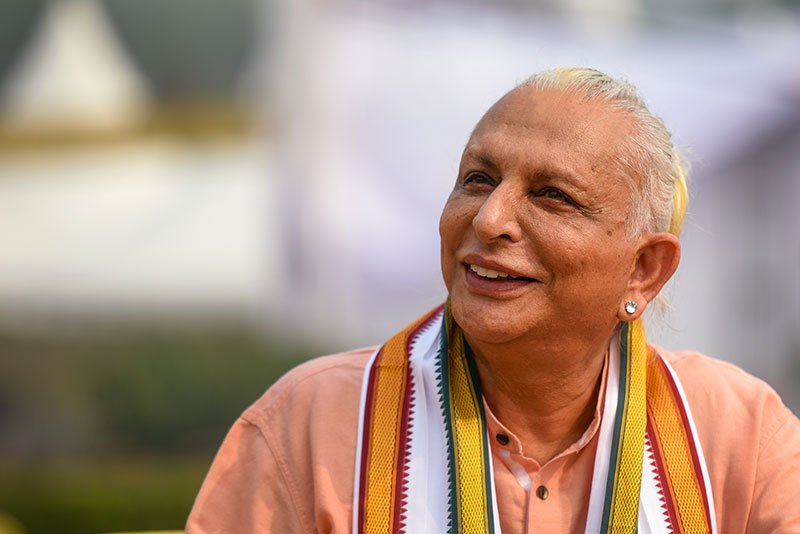

In fact, it is very difficult for you to distinguish a Yogi from a non-Yogi just from external paraphernalia and appearances. However, there is one key trait by which you can distinguish a Yogi. He or she—Yogi or Yogini—is in the words of the Bhagavad Gita, a Stitha Pragna.

Who is a Stitha Pragna? One who maintains equilibrium, mental equilibrium, under all circumstances. You cannot surprise a Yogi, make him angry, or disturb the tranquillity of his mind; no event can do that. That kind of balanced tranquillity of the mind is a result of the practice of Yoga.

Such a Yogi is called a Stitha Pragna. One whose consciousness has become Stitha, which means—steady, quiet, and tranquil.

You would be interested to know that the Bhagavad Gita, with its 18 chapters, is called a book of Yoga. Every chapter is called Yoga: Bhakti Yoga, Gnana Yoga, Karma Yoga, Sanyasa Yoga, and so on and so forth. In the last part of every chapter, the Gita states the phrase which is important for us to know, Yoga Shastrey, which means—it is a technique of Yoga which is being taught.

The practice, like every other practice, needs a background, or a philosophy, or a training blueprint. You just don’t start practising something without knowing. One, why are you practising it? Two, how to practice it? And, three, what is the aim of practising it, what do you hope to achieve by its practice? For this, one has to look at the most authoritative and ancient scriptures on Yoga—The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

How does Patanjali define Yoga? No matter what anybody else says, that should be a universal definition of Yoga. The first sentence of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra is ‘Yogas-Chitta-Vritti-Nirodha’, which means—Yoga is the stopping of the movement or the disturbances or vibrations of the mind-stuff. Yoga is the practice by which the mind, which is constantly moving up and down, in and out, this side and that side, is made to settle down; it becomes tranquil, motionless, and one-pointed. This is the basic aim of Yoga, and the results of advanced Yoga starts from this point. This is not the end point of Yoga but the starting point, which means—without this kind of tarmac or runway for the practitioner, there is no takeoff to the higher realms of consciousness. So, it is essential. It is learning to control and stop the movement of disturbing thought processes, so that the mind becomes like a ripple less body of water, on which is reflected the countenance of the divine. This is Yoga.

Patanjali calls his brand of Yoga, which of course is the most authoritative, ancient and legitimate Yoga—Ashtanga Yoga, which means—the Yoga of Eight Limbs. Ashta meaning eight and Anga meaning limbs or branches.

He lays down these branches starting with Yama and Niyama and ending with Samadhi, which is the altered state of consciousness—where the ordinary human being becomes a superhuman being, a Yogi or a Siddha Purusha. Yama, Niyama, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi. So it starts with rules and regulations —Yama, Niyama.

You cannot start the practice of Yoga without following at least a few simple procedures. One of the most important things is moderation. Not only moderation in eating and entertainment but moderation in everything—the middle path.

Krishna says in the Gita— ‘This yoga which I teach, is not for him who eats too much or who eats too little’. So these are the keywords—eats too much, or too little, Mitahara Vikarasaya, which means—to eat light food, controlled food, and also controlled indulgence in all activities of life.

Therefore, what they are trying to say is—make life simple, eat simple food, not fat producing food. If you eat fat producing food, it also produces cholesterol and you know the result of that. Eat too much and you will invariably fall asleep, same with eating too little, you cannot even think. So you have to strike a balance between the two.

Yama, Niyamas also include the practice of friendliness to all living beings. The practice of not causing injury to other living beings. The practice of not having too many things to do at the same time. Do one thing at a time. These are all unorthodox ways of describing Yama, Niyamas. But I am doing it because it is applicable today, to the modern human being. And then, of course, to spend more time exploring one’s mind than normal. If you follow these ground rules, you are kind of practising Yamas and Niyamas.

The next step is Asana. Asanas or postures, described in the books on Yoga, like the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, Goraksha Shataka and so on, which bring about physical and mental wellbeing.

A person who practices these Asanas regularly, usually automatically, eats little. He does not need too much and he is very light. He is not a burden with tonnes of fat on parts of his body; he can walk long distances. His voice becomes clear and since his body is healthy, he can also sit for a long time and meditate, because his mind is not distracted by the unhealthy condition of his body.

The Asanas are based on the principle that you cannot relax the body without tensing it, which means—if you have to, for instance, relax the muscles of your thigh, the best way is to first tighten the muscles, hold it tight for a while before letting go, and you will see how relaxed they become.

So, all the Asanas are based on first tightening the muscles, and the muscle fibres of the body, even on the spinal cord and then relaxing them, letting go, so that they are completely relaxed. When you practice Asanas, your spine is given a lot of attention. It either bends backwards or it bends forward in most Asanas. That kind of massages the spine and keeps the nerves of the spine, without any blockages caused by unnatural or improper posture.

Asanas are also meant to massage some of your ductless glands. For instance, a practitioner of Matsya-asana, if he has been doing it for quite some time, has very little chance of suddenly getting angry. Because anger is usually the pumping of adrenaline into the bloodstream and Matsya-asana massages that part of the ductless gland and keeps it from working overtime.

There are also some Asanas in which you stand on your head—Sirsasana for instance, the headstand—which improves the circulation of blood in your brain.

Such Asanas in fact, all Asanas, should only be done under the guidance of a proper teacher. And gradually, acquire the capacity to do them and not attempt to do all of them at once. It is nice to tie yourself up in knots, but the teacher should at least be there to untie you.

Once you have begun practising the Asanas, in general, your body’s health improves. And because of the massaging of certain glands, the mind also becomes healthy and tranquil.

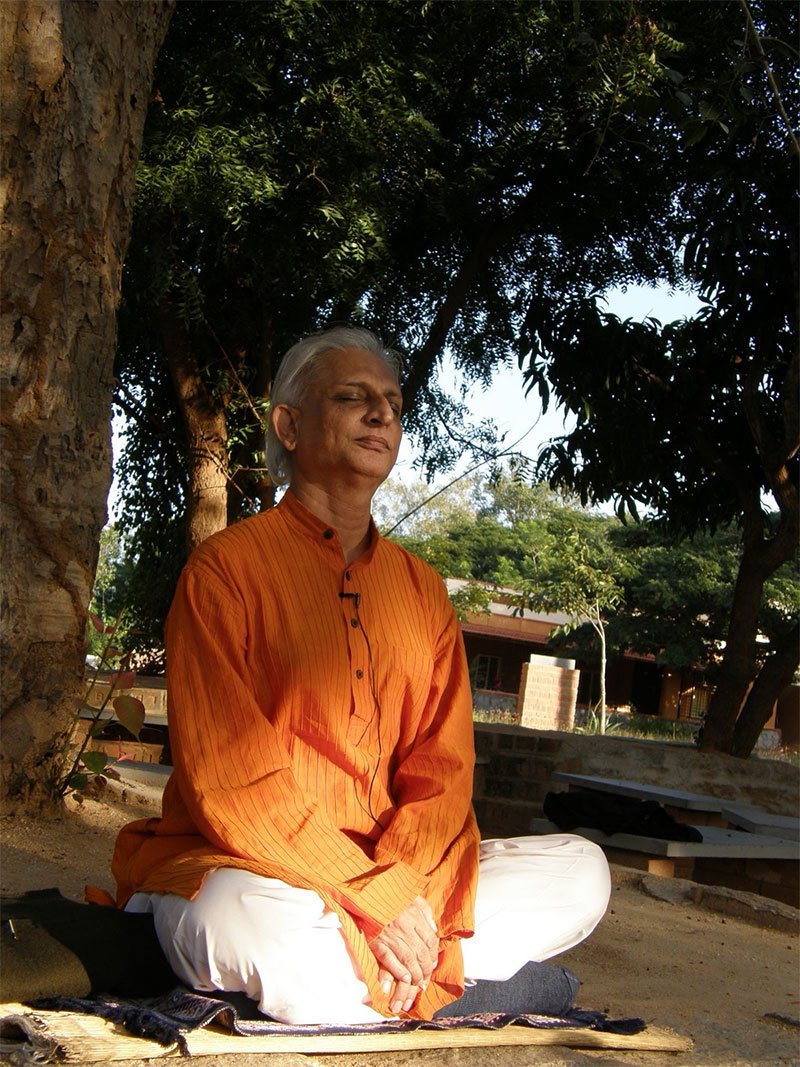

As far as meditation is concerned—which is the primary aim of Yoga, to bring about a calm state of mind—the most important Asana is the posture in which you sit when you meditate.

Patanjali has simply said, Sthiram Sukham Asanam. Any posture in which you can sit for a long period of time—in full comfort, without any discomfort—is considered to be your specific Asana. Padmasana— which is the lotus posture—the Buddha posture, Siddhasana, Sukhasana, Vajrasana, these are considered to be the usual postures used for meditation. However, if you find it difficult to sit in any of these poses, you may also sit in a chair, doesn’t matter. As long as you are not distracted and don’t feel pain and discomfort, it is fine. But keep your spine erect, and your body straight. Not tight or strained, but relaxed and straight. That would be your posture for meditation.

Now comes Pranayama. Prana means life energies. And Yama means the rules and regulations that govern the Prana; that governs the circulation of life energies in your physical body, in your system and also through your psychic channels.

Yoga lays a great deal of stress on Pranayama, which means—the practice of certain breathing techniques which are connected to your life energies— and by controlling the rate or the rhythm of your breathing, you are able to control the movement of life energies or Prana in your system. This is called Pranayama.

All the science of meditation that you hear of, which have come down to us from ancient times have all been the experiences of the rishis who are Yogis. They have experimented upon themselves and found the results and then given us the techniques. So, how does controlling your breathing help calm your mind? If that is the aim.

The great Rishis, the Yogis, discovered that the state of one’s mind very often influences the rhythm of one’s breathing, inhalation and exhalation. For instance, if one is in a calm state of mind—sitting under a tree, in a beautiful park, looking at the sea or at a river, or sitting in your favourite armchair, reading a novel, or even closing your eyes and listening to beautiful music—usually, if you observe your breathing pattern at such times, you will see that the pattern of your breathing is very slow, quiet and without distractions.

When you are agitated, angry, excited, tense or have exerted yourself too much, just watch the pattern of your breathing and you will find that the pattern of your breathing is also agitated, irregular, hard, fast and so on.

So the Yogis say—if the state of mind is reflected or connected in some way to the rhythm or pattern of breathing, is it possible that one can control one’s breathing rhythm or pattern to bring about a change in one’s state of mind? So they tried it and succeeded.

They found out that if the pattern of breathing, inhalation and exhalation, can be made calm, quiet, deep and slow, the thought process in your mind also becomes quiet, slow, steady and tranquil.

When the mind becomes tranquil, it is able to delve deep into the inner recesses of one’s consciousness and reach altered states of higher consciousness, which are otherwise impossible to reach.

Therefore, they worked out various formulae and ways of altering the state of your mind by practising certain rhythmic patterns of breathing, which also includes hyperventilation—fast breathing—and suddenly stopping the breath.

A calm state of mind—the means to reduce the number of thoughts to a minimum—brings about tranquillity. Most of our distractions are because of too many thoughts running hither and thither, up and down, this side and that.

One of the ways to bring about that tranquillity, is to not even try to control your breath—but to quietly observe your breath mentally. This is what is used in the famous Buddhist practice called Vipassana, which means—watchfulness or observation.

How do you do that? Very simple—sit in a quiet place, let there be fresh air if possible. I am saying, if possible, because we live at a time now when fresh air seems to come at a premium.

Wear clean and loose clothes, so that there is no bodily restriction in any part of your body. Sit straight, in any Asana or in a posture which keeps your spine steady. Then close your eyes. Direct your attention to the pattern of your breathing. As you breathe, direct your attention to your inhalation and exhalation, after a while, automatically, you will notice that your breathing has slowed down.

Usually, before this happens, you involuntarily give a deep sigh and then everything is settled, peaceful and calm. That is the time when you can watch your body mentally from the tip of your toes to the top of your head—giving attention to each part, bit by bit—meanwhile also giving attention to your inhalation and exhalation. Practice it and you will find out for yourself that very soon, you have come to a calm, peaceful and very often, blissful state of mind. This is Pranayama. Well, I would say, one of the ways of doing Pranayama.

After Pranayama comes Pratyahara. That is to develop the technique of switching on and switching off your thoughts at any given time. Which means, to be able to fix your attention on something when you require and to withdraw it when required.

This comes through the constant practice of Pranayama, which I have described to you just now. With constant practice of Pranayama, one gets the capacity for Pratyahara. Switch off and switch on. What more do we need? When you are working, you switch on. When we don’t want to, switch off. Usually we can’t because we are obsessed with that on which our mind is concentrated. Pratyahara is the way to be free of obsessions. And soon, even in life, you become free of obsessions.

Then comes Dharana. Dharana means the capacity to fix your attention on an object, a sound, an idea, an ideal, a form or a light. Anything to the exclusion of all other things, which means—if your mind has given complete attention to a sound, for instance, it should only be listening to that sound and not let it be distracted by anything outside. This is called Dharana.

This is also acquired through the practice of Pranayama. After the practice of Pranayama, when it matures into Pratyahara, one is able to do Dharana—to fix one’s attention exclusively on what one wants to.

This one-pointed attention is the beginning of meditation. Where there is no distraction of mind, and it becomes natural and painlessly simple to fix your attention on either something outside you or something inside you. When you are functioning in the physical world, it helps to fix your attention on something outside. When you are meditating, fix your attention within yourself. Either on your breath, light or a sound which is heard internally.

Actually, when the mind becomes quiet, you begin to hear some internal sounds. Like the cricket’s chirp, the ringing of a bell, or sometimes, like waves breaking upon the distant shore. Once you hear that, keep your attention fixed on it. And as you remain in it for a long time, the Dharana turns into Dhyana. The proper word for Meditation—Dhyana.

When Dhyana continues unobstructed for a long time—in that utter tranquillity, you suddenly come face to face with your true essence—which is pure consciousness, pure and simple. Which is why its very nature is blissful. The Yogis and the Vedantins called it Sachidananda. It is the truth, it is the nature of consciousness and it is blissful—Ananda. This is the aim of the practice of Yoga.

When I say aim, it means it is the beginning of the stage of the Yoga practitioner, where he begins to ascend to higher and higher levels of consciousness. That is the starting point, where the mind has become quiet and calm and is enjoying the bliss of that tranquillity within, independent of any external stimuli.

When the Yogi has attained that, he is supposed to have attained the practice of Yoga.

This need not discourage us, because it is possible for human beings to do this with a little or more effort, depending on one’s situation, background and other conditions that are there at that time.

Once such one-pointed tranquillity is achieved by the mind, it is possible to fix your attention on anything you want, to the exclusion of everything else. And attain that which you had started out to attain.

This capacity of the Yogi to successfully achieve the end is known as a Siddhi. Such a person develops extraordinary capacities and from a man, he becomes a superman.

With such extraordinary powers of concentration, the capacity to remain tranquil amid multiple circumstances, a person begins the journey towards higher consciousness, internally. And even success in his outer life or material mundane life, if he so wants.

The fact is that the Yogi who has reached this state is beyond all that the mundane world can offer because he has hit upon the very source of happiness and is independent of anything else. Such a Yogi, according to the philosophy of Yoga, is supposed to have attained Kaivalya, or release from pain or freedom from dependency. He or she is the only person who can be called an independent human being.

This is the aim of the practice of Yoga. Yogas-Chitta-Vritti-Nirodha!